Learn Faster, Remember Longer (Psychology-Backed)

Learning effectively isn’t about working harder—it’s about working smarter. After two decades as a Chartered Occupational Psychologist, I’ve seen countless people spend hours on material that simply won’t stick, or struggle through learning that takes far longer than necessary. The frustration is real: presentations you can’t recall without notes, skills that refuse to cement into place, information that takes weeks to learn when it should take days.

The good news? Both learning speed and memory retention can improve dramatically through specific, evidence-based techniques. Research shows that most people use inefficient learning strategies—not because they’re lazy, but because the most effective methods aren’t intuitive. Whether you’re developing professional skills, studying for exams, or simply wanting to learn more efficiently, understanding how your brain processes and stores information gives you practical tools to learn faster and remember longer.

This guide draws from cognitive psychology research and real-world application to show you what actually works. No gimmicks, no pseudoscience—just proven strategies you can implement today.

Understanding How Memory Works

Before diving into techniques, it’s worth understanding the basic architecture of memory. This isn’t just academic—knowing how your memory operates helps you choose the right strategies for different situations.

The Three Stages of Memory Formation

Every memory you form passes through three distinct stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Think of encoding as saving a file on your computer, storage as keeping it on your hard drive, and retrieval as opening it back up when needed.

The encoding stage is where most learning fails. Your brain receives thousands of pieces of information daily, but only a fraction gets encoded into memory. The techniques we’ll explore primarily target this encoding stage—they help your brain decide that information is worth keeping.

Storage happens largely without conscious effort, though sleep plays a crucial role in consolidating memories. The third stage—retrieval—is where many people discover their encoding wasn’t as solid as they thought. Information feels familiar but won’t surface when needed.

Working Memory vs. Long-Term Memory

Your brain uses two fundamentally different memory systems, and understanding the distinction matters for learning effectively.

Working memory is your mental workspace—it holds information temporarily while you use it. It’s remarkably limited, typically managing about four distinct pieces of information simultaneously. When you’re trying to follow complex instructions, remember a phone number long enough to dial it, or hold multiple thoughts in mind during a conversation, you’re using working memory.

Long-term memory, by contrast, has virtually unlimited capacity. Information stored here can last a lifetime. The challenge isn’t capacity—it’s getting information from working memory into long-term storage in a way that allows reliable retrieval later.

Most learning techniques work by either reducing the burden on working memory (through chunking or organisation) or strengthening the transfer from working to long-term memory (through repetition, elaboration, or association).

Evidence-Based Learning Techniques

Research consistently identifies certain techniques as significantly more effective than others. These aren’t the methods most people instinctively use—which explains why learning often feels harder than it should.

Active Recall and Retrieval Practice

Active recall is the single most powerful learning technique supported by research. Rather than reviewing information passively, you actively try to retrieve it from memory without looking at your notes.

This feels harder than rereading, which is precisely why it works. The effort of retrieval strengthens memory traces. Each time you successfully pull information from memory, you make it easier to retrieve next time. When you fail to retrieve something, you identify exactly what you haven’t learned properly.

Practical implementation is straightforward: after reading a section of material, close your notes and write down everything you remember. Use flashcards where you test yourself rather than simply reviewing. When learning a skill, test your ability to perform it rather than just watching demonstrations.

The discomfort is the point. If active recall feels easy, your brain isn’t doing the work that builds lasting memory.

Spaced Repetition Systems

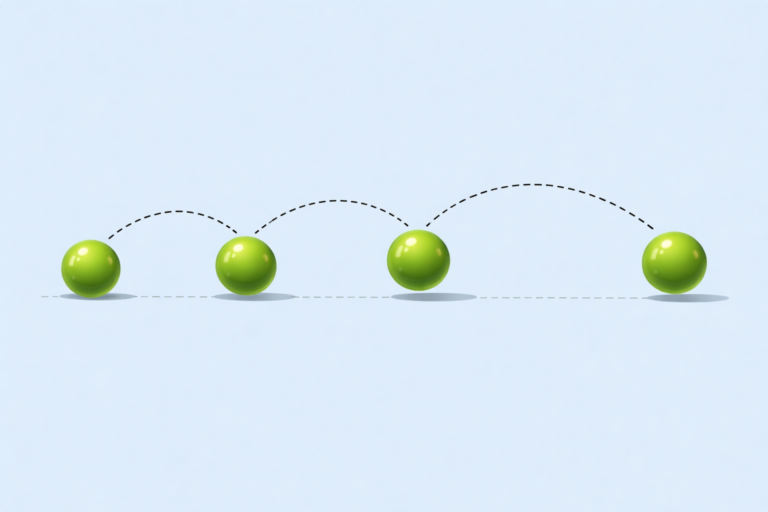

The forgetting curve—discovered by Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885—shows that we forget most new information rapidly within the first 24 hours, then more gradually over time. Spaced repetition exploits this pattern by reviewing information just as you’re about to forget it.

The optimal spacing isn’t intuitive. You might review material after one day, then three days, then a week, then three weeks, then several months. Each successful retrieval pushes the next review further into the future. Information reviewed too frequently wastes time; reviewed too infrequently, and you’ve already forgotten it.

This spacing effect is remarkably powerful. Research shows that distributed practice produces substantially better long-term retention than massed practice (cramming), even when total study time is identical. Your brain needs time between exposures to consolidate information properly.

Digital tools like Anki automate the scheduling, but you can implement spaced repetition manually with a simple calendar system. The key is resisting the urge to review material when it still feels fresh—that’s when your time is least effective.

Elaborative Rehearsal

Elaborative rehearsal means processing information deeply by connecting it to existing knowledge, asking questions about it, and thinking through its implications. It’s the opposite of mindless repetition.

When you encounter new information, ask yourself: How does this relate to what I already know? Why does this work this way? What are the practical implications? Can I think of an example from my own experience? These questions force deeper processing that creates stronger, more retrievable memories.

The self-reference effect demonstrates this powerfully. Information becomes more memorable when you relate it to yourself. A fact about human behaviour is more memorable when you consider whether it applies to your own life. A business concept sticks better when you think through how you’d apply it in your work.

This takes more time initially but dramatically reduces the total time needed to learn something well. Shallow processing requires endless repetition; deep processing often requires just one or two exposures.

Dual Coding Theory

Your brain processes visual and verbal information through different pathways. Dual coding theory, developed by Allan Paivio, shows that information encoded both visually and verbally is more memorable than information encoded in only one way.

This explains why diagrams, sketches, and mind maps enhance learning—not because they look nice, but because they give your brain an additional retrieval path. When you can’t quite recall the verbal explanation, the visual representation might trigger the memory, and vice versa.

Practical application doesn’t require artistic skill. Simple sketches, basic diagrams, or even just spatial organisation of information on a page engages visual processing. The act of converting verbal information into visual form also forces deeper thinking about the material.

Efficient Learning Strategies

Memory techniques help you retain what you’ve learned, but learning speed depends on how efficiently you process information in the first place. These strategies help you learn faster without sacrificing depth or retention.

Identifying High-Value Information

One of the biggest time-wasters in learning is treating all information as equally important. Textbooks contain core concepts, supporting details, examples, and filler. Lectures include key principles alongside tangential discussions. Not everything deserves equal attention.

Develop the skill of distinguishing signal from noise. Look for information that appears repeatedly—authors and instructors emphasise what matters by returning to it. Notice structural cues: section headings, summary boxes, “importantly” or “the key point is…” markers. Pay attention to what’s tested or applied practically.

When reading, scan the chapter structure before diving in. Read the introduction and conclusion first—they typically highlight core concepts. Then decide which sections warrant deep reading versus quick skimming. This strategic approach saves hours compared to treating every paragraph identically.

In professional learning, ask explicitly: “What’s the 20% that produces 80% of the results?” What information will you actually use? What knowledge enables everything else? Focus your deep processing there, and give lighter attention to supporting details you can reference later if needed.

The Feynman Technique for Understanding

Named after physicist Richard Feynman, this technique forces genuine understanding rather than superficial familiarity. The process is straightforward: take a concept you’re learning and explain it in simple language as if teaching someone with no background knowledge.

The magic happens when you get stuck. If you can’t explain something simply, you don’t understand it properly—you’ve just memorised jargon. The gaps in your explanation reveal exactly what you haven’t grasped. You then return to source material specifically targeting those gaps.

This technique prevents the illusion of knowledge—that feeling of understanding something when reading about it, only to discover you can’t actually explain or apply it. By forcing explanation in your own words, you identify these gaps immediately rather than discovering them later when it matters.

The technique works particularly well for complex or technical material. Rather than reading and rereading until material “feels” familiar, read once, then immediately try explaining it. Your failed explanation tells you exactly what to focus on next. This targeted approach learns faster than passive repetition.

Progressive Summarisation

Progressive summarisation, developed by Tiago Forte, compresses information through successive passes, each time extracting only what’s most important. This creates efficient learning and excellent reference material.

The first pass captures information comprehensively—detailed notes or highlights from source material. The second pass bolds or highlights the most important points within your notes—perhaps 20% of the content. A third pass might bold the most critical insights within your already-highlighted material.

Each pass forces you to process information more deeply: “What’s truly essential here?” This progressive compression serves two purposes. First, the act of summarising builds understanding through elaborative processing. Second, you create layered notes where the most important information is immediately visible, but supporting details remain accessible.

This particularly suits professional learning where you’re building knowledge bases for long-term reference. Your notes become increasingly valuable over time as progressive summarisation reveals core principles while maintaining detailed support when needed.

Strategic Reading: When to Skim vs. Deep Dive

Reading everything at the same pace wastes enormous time. Different material demands different reading strategies, and efficiency comes from matching strategy to content and purpose.

Skim when you’re surveying a field, looking for specific information, or dealing with low-value content. Skimming isn’t lazy reading—it’s strategic reading. Your eyes move quickly, catching keywords, headings, topic sentences, and conclusions. You’re building a mental map of content location rather than absorbing details.

Deep reading applies when you’ve identified high-value content, when material is genuinely difficult, or when you need thorough understanding for application. Here, you slow down, reread difficult passages, take notes, and actively process meaning. Deep reading after strategic skimming is far more efficient than deep reading everything indiscriminately.

For books, read the introduction and conclusion first, then skim chapter beginnings and endings. This reveals structure and main ideas. Then decide which chapters deserve deep reading, which merit skimming, and which you can skip entirely. You might deeply read 30% of a book and still extract 80% of the value.

For articles or papers, the abstract and conclusion typically contain core findings. The introduction explains why it matters. The methodology can often be skimmed unless you need to evaluate research quality. Results and discussion sections deserve attention proportional to how directly they address your learning goals.

Learning Speed Multipliers

Beyond general strategies, specific practices dramatically accelerate learning when implemented consistently. These are force multipliers that compound over time.

Effective Note-Taking Methods

How you take notes during learning significantly affects both immediate comprehension and later retention. Most people’s instinct—transcribing information verbatim—is actually counterproductive.

Effective note-taking requires processing information actively rather than passively recording it. The Cornell method divides pages into sections: main notes, cues/questions in the margin, and summary at the bottom. During learning, you take normal notes. Afterwards, you generate questions or keywords in the margin that would cue those notes. Finally, you write a brief summary from memory.

This structure forces active processing three times: during initial encoding, when creating cues, and when summarising. Each processing pass strengthens understanding and retention more effectively than passive review ever could.

Mind mapping works brilliantly for interconnected information. Rather than linear notes, you create visual networks showing relationships between concepts. The spatial organisation aids memory through dual coding, while the act of deciding how concepts relate builds deeper understanding.

For procedural learning or step-by-step processes, flowcharts and diagrams often capture information more efficiently than text. A well-designed diagram can communicate in seconds what paragraphs of text explain laboriously.

Digital note-taking enables linking between notes, creating a personal knowledge web. Apps like Obsidian or Notion let you connect related concepts across different learning sessions, building an external thinking environment that supplements your memory.

Reducing Cognitive Load

Your working memory has limited capacity—typically handling about four chunks of information simultaneously. When learning pushes beyond this limit, comprehension collapses. Reducing cognitive load lets you learn faster by keeping information processing within capacity.

Chunking is the fundamental technique. Rather than remembering seven individual items, group them into two or three meaningful chunks. Phone numbers use this instinctively: 07700900461 is harder than 07700 900 461. The same digits become more manageable when chunked appropriately.

External storage prevents working memory overload. When learning complex material, use paper or a whiteboard to hold information you’re working with. Writing down intermediate steps in calculations, key points from earlier in a lecture, or frameworks you’re applying frees working memory for actual processing rather than storage.

Reduce unnecessary cognitive load by eliminating distractions. Background music with lyrics, nearby conversations, or visible notifications all consume working memory capacity needed for learning. Create an environment where your limited cognitive resources can focus entirely on the learning task.

Break complex learning into manageable pieces. Trying to understand an entire complex system at once overwhelms working memory. Instead, understand one component thoroughly, then another, then how they connect. This sequential approach respects cognitive limitations while building toward comprehensive understanding.

Pattern Recognition and Mental Models

Expert learners learn faster because they recognise patterns quickly. Novices see isolated facts; experts see relationships, principles, and structures. Developing pattern recognition and mental models accelerates all future learning in that domain.

Mental models are frameworks for understanding how things work. In business, you might have models for market dynamics, organisational behaviour, or decision-making. In psychology, models for memory, motivation, or behaviour change. These models let you quickly assimilate new information by fitting it into existing frameworks.

Build mental models deliberately. When learning something new, explicitly ask: “What’s the underlying structure here? What’s the general principle? How is this similar to something I already understand?” These questions help you extract transferable patterns rather than isolated facts.

Analogies and metaphors accelerate pattern recognition. “Working memory is like a desk—limited surface area for active work, while long-term memory is like filing cabinets with unlimited storage.” The analogy provides instant understanding that paragraphs of abstract explanation might not achieve.

Compare and contrast similar concepts. Understanding the differences between similar things (working vs. long-term memory, proactive vs. retroactive interference, encoding vs. retrieval) builds precise mental models. This precision prevents confusion and enables accurate application.

Optimal Learning Conditions

When you learn matters almost as much as how you learn. Your brain’s capacity for encoding new information varies significantly based on physiological and environmental factors.

Chronotype affects optimal learning times. If you’re a morning person, tackle difficult conceptual learning early. If you’re an evening person, don’t force intensive learning at 8am—you’re fighting biology. Match learning demands to your natural energy and focus patterns.

Physical state dramatically impacts learning capacity. Hunger, dehydration, or physical discomfort all impair cognitive function. Ensure basic physiological needs are met before demanding intensive learning from your brain. A 15-minute walk before learning often improves subsequent performance through increased blood flow and alertness.

Environmental factors—lighting, temperature, noise levels—affect learning efficiency more than most people realise. Uncomfortably warm rooms impair concentration. Poor lighting causes fatigue. Find your optimal environment and protect it during learning sessions.

The most underrated learning optimiser is taking actual breaks. The Pomodoro Technique (25 minutes focused work, 5 minute break) works because your brain needs recovery time. Trying to maintain focus for hours without breaks produces steadily declining returns. Better to work intensively for shorter periods with genuine breaks between.

Memory Techniques for Specific Situations

General principles are useful, but specific situations often demand specialised approaches. Here’s how to apply memory science to common challenges.

Remembering Names and Faces

Name recall fails for a specific psychological reason: names are arbitrary labels with no inherent meaning. Your brain evolved to remember meaningful information, not random associations between faces and sounds.

The most effective technique creates artificial meaning through association. When you meet someone named Martin, you might visualise them in a martial arts uniform (if that creates a memorable image for you). Meeting Sarah? Perhaps she’s eating a piece of Sarah Lee cake. The associations needn’t be sophisticated—just distinctive and personally meaningful.

Repetition matters too, but not mindless repetition. Use the person’s name naturally in conversation within the first few minutes: “Martin, what brings you to the conference?” The immediate rehearsal strengthens initial encoding when forgetting is most rapid.

Context helps tremendously. When possible, encode environmental cues along with the name: “Martin from the corner office” or “Sarah who sits by the window.” Your brain retrieves contextual information more readily than isolated facts.

Memorising Presentations

Professional presentations require a different approach than word-for-word memorisation. Attempting to memorise every word creates a fragile memory that falls apart if you lose your place. Instead, you want to remember key points and natural transitions.

Chunking works brilliantly here. Break your presentation into 3-5 main sections, each containing 3-4 key points. This hierarchical structure matches how your brain naturally organises information. You remember the structure, and the structure cues the details.

The journey method (a variation of the memory palace technique) lets you anchor presentation sections to familiar locations. Imagine walking through your house: the introduction happens at your front door, the first main point in your living room, the second in your kitchen, and so on. During delivery, mentally retracing this path cues each section naturally.

Practise with active recall—not by rereading your notes or slides. Stand up and deliver sections from memory, then check what you missed. This identifies weak spots while strengthening retrieval pathways. Space these practice sessions out over several days before your presentation.

Learning New Skills

Skill acquisition follows different rules than fact memorisation. Motor skills and procedures require building automatic responses, not just storing information.

Deliberate practice—coined by Anders Ericsson—forms the foundation. This means practising at the edge of your current ability, getting immediate feedback, and focusing on your weakest areas. Comfortable practice maintains existing skill but doesn’t build new capability.

Mental practice supplements physical practice surprisingly effectively. Research with musicians, athletes, and surgeons shows that visualising performance activates similar neural pathways as actual performance. When you can’t physically practise, mentally rehearsing the skill maintains and even improves capability.

Spacing applies to skills as much as facts. Four 30-minute practice sessions spaced over four days produces better results than a single two-hour session. Your brain needs time between sessions to consolidate motor patterns and integrate feedback.

The Science Behind Memory Enhancement

Understanding why techniques work helps you adapt them to your specific needs and maintain motivation when initial progress feels slow.

Sleep and Memory Consolidation

Sleep isn’t just rest—it’s when your brain actively processes and integrates new information. During deep sleep, your brain replays experiences from the day, transferring information from temporary storage into long-term memory.

Research shows that learning material before sleep leads to better retention than learning it earlier in the day. This isn’t about reviewing notes in bed—it’s about the timing of initial encoding. Your brain naturally consolidates recent learning during subsequent sleep.

Different sleep stages consolidate different types of memory. REM sleep (when dreaming occurs) primarily consolidates procedural memories—skills and motor sequences. Deep sleep consolidates declarative memories—facts and concepts. This is one reason why sleep deprivation so dramatically impairs learning.

Strategic napping can enhance learning too, particularly naps containing deep sleep (90+ minutes) or short naps (10-20 minutes) that don’t leave you groggy. The key is timing: napping after intensive learning enhances consolidation, while napping before learning refreshes working memory capacity.

Why We Forget (and How to Prevent It)

Forgetting isn’t a failure of memory—it’s a feature. Your brain actively discards information that seems unimportant. Understanding why forgetting occurs helps you fight it effectively.

Decay theory suggests memories simply fade over time without use, like muscles weakening without exercise. There’s truth here: unused memories do become harder to retrieve. But retrieval practice keeps them accessible. The occasional review maintains long-term retention far more efficiently than continued intensive study.

Interference causes more forgetting than simple decay. New learning interferes with old (retroactive interference), and old learning interferes with new (proactive interference). This is why similar topics are particularly hard to keep straight—they compete for the same retrieval cues.

Combat interference by making memories distinctive. Rather than learning similar concepts back-to-back, space them out. Explicitly note differences between easily confused items. Use different study environments or times of day to provide distinct contextual cues.

Context-dependent forgetting occurs when retrieval context differs from encoding context. You learn something in one setting but can’t recall it in another. This matters more for examination conditions than real-world application, but the principle is worth understanding: practising retrieval in varied contexts builds more flexible, accessible memories.

Practical Implementation

Knowing techniques is useless without implementing them. Here’s how to build an effective personal learning system.

Building Your Learning System

Start simple. Pick one or two techniques that address your biggest challenge. Trying to implement everything simultaneously guarantees implementation failure.

If retention is your main problem, begin with active recall. After any learning session, close your materials and write down everything you remember. This single change produces dramatic results.

If you forget material within days or weeks, implement spaced repetition. Create a simple review schedule: review new material after one day, three days, one week, two weeks, one month. Adjust based on your results.

For complex material that won’t stick, use elaborative rehearsal. For every new concept, write down: how it connects to what you already know, why it matters, and one example from your own experience. This deeper processing pays dividends.

Tools and Apps That Support Memory

Technology can enhance learning when used properly. Spaced repetition apps like Anki automate optimal review scheduling. Note-taking apps like Obsidian or Notion support elaborative techniques through linking and organisation. Mind mapping software helps with dual coding and visual thinking.

But tools aren’t necessary. Index cards, a notebook, and a calendar implement every technique we’ve discussed. The danger with apps is treating them as magic solutions rather than tools that still require the difficult work of encoding information properly.

Choose tools based on the techniques you’re using, not the other way around. If you’re not using spaced repetition, don’t start with Anki and hope it somehow transforms your learning. Start with the technique manually until it becomes habitual, then consider whether a tool would help.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

The biggest mistake is confusing familiarity with learning. Rereading notes until material feels familiar doesn’t mean you’ve learned it—it means you’re good at recognising it. Test yourself instead. If you can’t generate information without prompts, you haven’t learned it yet.

Cramming persists despite overwhelming evidence it doesn’t work for long-term retention. You might pass tomorrow’s test through intensive last-minute study, but you won’t remember the material next month. If your goal is genuine learning rather than short-term performance, spacing is non-negotiable.

Over-highlighting and over-noting suggests activity without the cognitive effort that produces learning. Taking extensive notes during a lecture often prevents you from thinking about the content. Better to engage actively with material, then summarise key points from memory afterwards.

Multitasking during learning sessions seems efficient but fragments attention. Your brain can’t encode information effectively while monitoring email, texts, or background videos. Learning requires focused attention. Save multitasking for tasks that don’t require encoding new information.

Adapting Techniques to Your Context

Not every technique suits every situation. Professional learning differs from academic study, which differs from skill development. Here’s how to adapt approaches appropriately.

For professional knowledge that changes regularly, focus on understanding principles over memorising details. Use elaborative rehearsal to build mental models that let you reconstruct information as needed. You don’t need to memorise every workplace procedure if you understand the underlying logic.

For academic learning, combine active recall with spaced repetition. Past exam questions are perfect active recall practice. Space your study over weeks or months rather than cramming before exams. The research is unequivocal: spaced practice produces better long-term retention and often better immediate performance too.

For skill acquisition, prioritise deliberate practice with immediate feedback. Mental practice supplements physical practice when you can’t access the actual task. Space practice sessions to allow consolidation. Push yourself to slightly harder challenges as skills develop.

For casual learning—keeping up with your field, general knowledge, personal interests—active recall still matters. Explain concepts to others, write summaries from memory, or maintain a personal knowledge base that you update and review periodically.

Maintaining Motivation and Managing Expectations

Even the best techniques require sustained effort. Understanding the learning process helps maintain motivation when progress feels slow.

Learning follows a predictable curve. Initial progress comes quickly as you pick up fundamental concepts. Then progress slows—you hit a plateau. This plateau doesn’t mean techniques have stopped working; it means you’re consolidating knowledge and preparing for the next jump in capability. Plateaus are normal, not failures.

Set process goals rather than just outcome goals. “I will test myself on this material for 30 minutes daily” is more actionable and motivating than “I will master this topic.” You control the process; outcomes follow from consistent process.

Track your progress explicitly. Keep a simple log of study sessions and test results. When motivation flags, reviewing your log shows progress that daily experience might obscure. Small improvements compound dramatically over time.

Rest matters as much as effort. Breaks between study sessions aren’t wasted time—they’re when consolidation occurs. Working to exhaustion produces diminishing returns. Better to study focused for 45 minutes, take a proper break, then return refreshed than to slog through three hours of degraded attention.

Conclusion: Learning Faster and Remembering Longer

Effective learning isn’t about being born with natural talent or grinding through endless hours of study. It’s about understanding how your brain processes information and using strategies that align with cognitive architecture.

Learning speed comes from efficient information processing: identifying what matters, using techniques like the Feynman method to build genuine understanding, reducing cognitive load, and creating optimal conditions for focus. Memory retention comes from proper encoding strategies—active recall, spaced repetition, elaborative rehearsal, and dual coding.

These aren’t separate skills. Learning faster means nothing if you forget everything immediately. Strong memory is wasted if learning takes far longer than necessary. The techniques in this guide work together—efficient learning creates better initial encoding, making memory techniques more effective.

Start with one or two strategies that address your biggest challenge. If you’re learning too slowly, focus on identifying high-value information and using the Feynman technique. If retention is your problem, implement active recall and spaced repetition. Build competency in foundational techniques before adding others.

The improvement won’t be instant—learning techniques work through cumulative effect—but you’ll notice differences within days of proper implementation. Information will stick more reliably. Learning sessions will feel more productive. Skills will develop faster.

Your brain is more capable than you think. Give it the right conditions—efficient processing strategies, proper encoding techniques, spaced practice, adequate sleep—and you’ll be surprised what you can learn and retain. The investment in understanding how learning and memory work pays dividends across every area that requires acquiring and applying knowledge, which is to say, across your entire life.

Simon Shaw is a Chartered Occupational Psychologist with over 20 years of experience in workplace learning and development. He has designed evidence-based training programmes for organisations across the UK and specialises in translating cognitive psychology research into practical applications for professional skill development.

I'm Simon Shaw, a Chartered Occupational Psychologist with over 20 years of experience in workplace psychology, learning and development, coaching, and teaching. I write about applying psychological research to everyday challenges - from habits and productivity to memory and mental performance. The articles on this blog draw from established research in psychology and behavioural science, taking a marginal gains approach to help you make small, evidence-based changes that compound over time, allowing you to make meaningful progress in the areas you care about most.