Habit Stacking Explained: The Simple Way to Build New Habits in 2026

You want to meditate more, read daily, exercise regularly, drink more water, and practise gratitude. But trying to build five new habits simultaneously feels overwhelming, and you inevitably abandon most of them within days. There’s a better way.

Habit stacking is a powerful technique that allows you to build multiple new behaviours by anchoring them to habits you already perform automatically. Instead of relying on motivation or remembering to do things “when you have time,” you create a chain of behaviours where each action triggers the next, making consistency almost effortless.

In this guide, I’ll explain the science behind why habit stacking works so effectively, show you how to design your own habit stacks, and provide practical examples you can implement immediately to transform your daily routine.

What Is Habit Stacking?

Habit stacking is a behaviour change strategy where you attach a new habit to an existing one using a simple formula: “After I [existing habit], I will [new habit].” This technique, popularised by James Clear in Atomic Habits, leverages habits you already perform automatically as triggers for behaviours you want to develop.

The concept builds directly on the cue-routine-reward structure of the habit loop. Every habit you’ve already established has a clear endpoint—a moment when one behaviour finishes. Habit stacking uses these endpoints as cues for new behaviours, creating chains where completing one action automatically prompts the next.

Rather than trying to remember new habits in isolation or waiting for motivation to strike, you’re piggybacking on your brain’s existing neural pathways. Because you already perform the existing ‘anchor’ habit automatically, the mental effort required to remember and execute the new behaviour drops dramatically. You’re not creating a new routine from scratch; you’re extending an existing one.

QUICK WIN:

Right now, write down three things you do automatically every day without thinking (brushing teeth, making coffee, sitting at your desk). Pick one and decide on the tiniest new habit you could attach to it. Example: “After I pour my coffee, I will write one sentence in my journal.” That’s your first habit stack.

The Science Behind Sequential Habits

Habit stacking works because of how your brain remembers behaviours in sequences. Research in neuroscience shows that when you consistently perform actions in a specific order, your brain begins to log the entire sequence as a single “chunk” of behaviour. This chunking process is the same mechanism that allows you to tie your shoes or type on a keyboard without consciously thinking about each individual movement.

When you stack habits, you’re deliberately creating these sequences of behaviours. Each time you complete the sequence—existing habit followed by new habit—you strengthen the neural pathway connecting them. After sufficient repetition, the completion of your existing habit begins to feel incomplete without the new, stacked habit that follows. Your brain has learned that the two actions go together.

This neurological linking explains why habit stacking often feels easier than building isolated habits. You’re not fighting to remember a new behaviour; instead, you’re working with your brain’s natural tendency to automate actions that often happen one after the other. The existing habit provides both a trigger and a sense of momentum that carries you into the new habit.

How Habit Stacking Differs from Regular Habit Formation

Traditional habit formation typically focuses on creating a single new behaviour triggered by environmental cues like time, location, or preceding events. You might decide to meditate at 7am, exercise when you arrive at the gym, or read before bed. These approaches can work, but they require remembering when and where to perform the new behaviour.

Habit stacking simplifies this process by using your existing automatic behaviours as incredibly reliable cues. You don’t need to remember to meditate at a specific time; you meditate immediately after you brush your teeth, something you already do without thinking. The cue is built into your routine rather than depending on your memory or a particular context.

Additionally, habit stacking naturally leads to building multiple habits more efficiently than traditional methods. Once you understand the principle, you can extend existing stacks or create multiple stacks throughout your day, systematically adding new behaviours without overwhelming your capacity for change. Each successful stack creates a platform for the next one.

Creating Your First Habit Stack

Building an effective habit stack requires more than simply deciding to add new behaviours to your routine. Success depends on choosing the right anchor habits, designing appropriate new behaviours, and implementing the stack strategically. See our complete guide to habit formation for more about creating habits.

Identifying Strong Anchor Habits

The foundation of any habit stack is the anchor habit—the existing behaviour that will trigger your new routine. Not all current habits make equally effective anchors. The best anchors share several characteristics that make them reliable triggers for new behaviours.

Strong anchor habits occur at consistent times in predictable contexts. Brushing your teeth, making your morning coffee, sitting down at your desk, or getting into bed at night happen daily in roughly the same circumstances. This consistency makes them dependable triggers that won’t vary from day to day.

Effective anchors are also highly automatic. You don’t need to remember to brush your teeth or decide whether to make coffee—these behaviours have become so ingrained that you perform them without conscious thought. This automaticity ensures the anchor will reliably occur, providing a consistent cue for your new habit.

The anchor should have a clear endpoint. Ambiguous activities like “working” or “relaxing” don’t provide distinct moments when you’ve finished. Instead, look for specific completions: putting down your toothbrush, pressing start on the coffee maker, closing your laptop, or turning off your bedside lamp. These definitive endpoints create obvious transitions where new behaviours can slot in naturally.

Examples of strong anchor habits include: pouring your first cup of coffee, sitting down for lunch, arriving home from work, finishing dinner, putting your child to bed, getting into the shower, or plugging in your phone to charge. Map out your typical day and identify the automatic behaviours that occur reliably each day.

Designing the Stacked Habit

Once you’ve identified your anchor habit, the next step is crafting the new behaviour you’ll attach to it. The design of this stacked habit determines whether the stack succeeds or fails, making this stage crucial to get right.

Start small—smaller than seems worthwhile. If you want to build a meditation practice, don’t stack “meditate for 20 minutes” onto your morning routine. Instead, stack “take three conscious breaths” or “sit on my meditation cushion for one minute.” The goal initially isn’t to achieve your ultimate objective but to establish the behaviour chain itself.

This minimal approach might feel inadequate when you’re motivated and enthusiastic about change. Resist the temptation to overreach. A tiny habit you perform consistently will grow naturally over time, whilst an ambitious habit you skip regularly trains the pattern of not doing the behaviour. Once the stack becomes automatic, you can gradually increase the intensity or duration.

The stacked habit should also have a natural fit with the anchor. Some behaviours flow logically from their anchors, while others feel forced. After making coffee, doing a few stretches flows naturally, but sorting the laundry might feel awkward. After turning off your laptop at day’s end, reviewing your task list for tomorrow makes sense, but jumping straight into exercise might require too much of a transition.

Consider the physical context as well. If your anchor habit occurs in your kitchen, your stacked habit should either happen in the kitchen or require minimal movement to begin. Creating stacks that require moving to a different room or gathering supplies adds friction that can derail the sequence.

Writing Your Habit Stack Formula

The specific language you use to define your habit stack matters more than you might expect. Precise formulation creates clarity that vague intentions don’t provide. Use this template to craft your stack:

“After I [existing habit], I will [new habit] in/at [location].”

Examples of properly formatted habit stacks include:

“After I pour my morning coffee, I will write three sentences in my journal at the kitchen table.”

“After I sit down at my desk, I will spend two minutes reviewing my priorities in my notebook.”

“After I put my dinner plate in the dishwasher, I will do ten press-ups in the kitchen.”

“After I close my laptop at the end of the workday, I will spend one minute tidying my desk.”

“After I get into bed, I will read one page of my book on the nightstand.”

Notice the specificity in these formulations. They identify exactly when the new behaviour happens (after the completion of a specific action), exactly what you’ll do (a concrete, measurable action), and exactly where you’ll do it (a defined location). This precision eliminates ambiguity and makes execution almost automatic.

Advanced Habit Stacking Strategies

Once you’ve mastered basic habit stacking with simple pairs of behaviour, you can employ more sophisticated strategies to build comprehensive routines that transform your entire day.

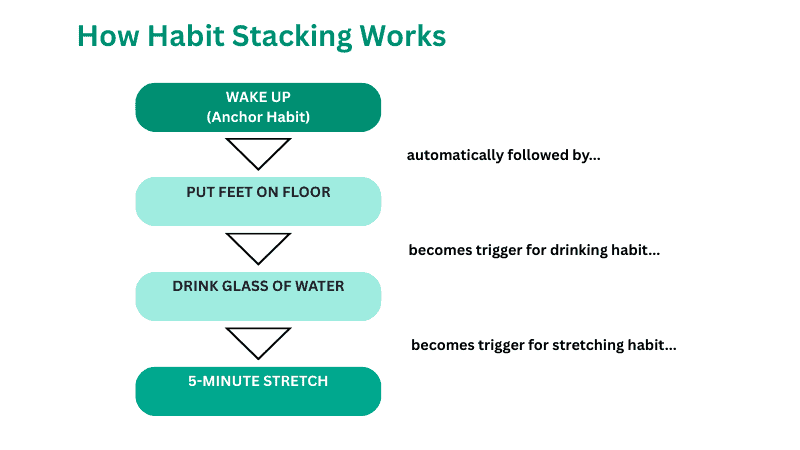

Building Extended Stacks

After establishing a successful two-behaviour stack, you can extend it by adding additional habits to create longer sequences. Instead of just pairing one new habit with one anchor, you create chains where multiple behaviours flow seamlessly from one to the next.

An extended morning stack might look like: “After my alarm goes off, I will put my feet on the floor. After I put my feet on the floor, I will drink a glass of water. After I drink water, I will do five minutes of stretching. After I stretch, I will meditate for two minutes. After I meditate, I will write three sentences in my journal.”

This chain transforms your morning from a series of isolated decisions into a single routine where each action naturally leads to the next. The momentum from completing one small step carries you forward into the next, reducing the willpower required to get through the entire sequence.

However, longer stacks require more care in construction. Each link in the chain must be strong enough to reliably trigger the next behaviour. If any individual habit in the sequence is too difficult or doesn’t fit naturally with its trigger, the entire chain can break down. Start with short stacks of two or three behaviours, allow them to become automatic, and only then extend them further.

Creating Multiple Stacks Throughout Your Day

Rather than building one enormous habit stack, a more sustainable approach is to create several smaller stacks distributed across your day. Different times and contexts provide natural opportunities for different types of habits, allowing you to systematically build a comprehensive set of new behaviours without overwhelming yourself.

A morning stack might focus on starting your day positively: water, movement, and planning. A midday stack could support productivity: reviewing priorities and preparing for afternoon work. An evening stack might emphasise recovery and preparation: exercise, healthy dinner, and setting up for the next day. A bedtime stack could promote rest: reading, gratitude, and creating good sleep conditions.

This distributed approach has several advantages. Different stacks can serve different purposes: you spread the mental load of building new habits across the day rather than concentrating it in one period, and if one stack falls apart temporarily, your other stacks remain intact, maintaining some of your positive momentum.

When designing multiple stacks, ensure each one anchors to a genuinely automatic existing habit that occurs reliably each day. Don’t create six different stacks all triggered by “when I have time” or “when I remember.” Each stack needs a solid, non-negotiable anchor that happens regardless of how your day unfolds.

Combining Habit Stacking with Other Techniques

Habit stacking becomes even more powerful when combined with other behaviour change principles. These combinations create synergistic effects that accelerate habit formation and increase your odds of long-term success.

Habit stacking plus environment design: Arrange your physical space to support your stacks. Place your journal next to your coffee maker, keep your yoga mat in your bedroom where you’ll see it immediately after waking, or position your book on your pillow so you encounter it when getting into bed. These environmental cues reinforce your stacks and remove friction.

Habit stacking plus temptation bundling: Pair behaviours you need to do with ones you want to do. “After I start the washing machine, I will listen to my favourite podcast while folding yesterday’s laundry.” The enjoyable activity (podcast) makes the necessary task (laundry) more appealing and reinforces the stack.

Habit stacking plus social commitment: Share your stacks with others or create parallel stacks with family members. “After we finish dinner, we will each share one thing we’re grateful for.” The social element adds accountability and makes the behaviour more rewarding.

Habit stacking plus tracking: After completing a stack, track it. Tracking can be physical, like immediately marking it on a calendar or digital in a habit tracking app. The tracking element becomes the final part of the habit stack – “After I complete my morning stack, I will put an X on my wall calendar” or “After I complete my morning stack, I will log it in my tracking app.” This creates a visual record of your consistency and provides an immediate sense of accomplishment.

Common Habit Stacking Mistakes

Even with a clear understanding of the technique, people commonly make errors that undermine their habit stacks. Understanding why habits fail helps you avoid them and build stacks that actually stick.

Choosing Weak Anchors

The most frequent mistake is selecting anchor habits that aren’t truly automatic or don’t occur consistently. If your anchor habit is “after I feel motivated” or “when I have free time,” you don’t have a real anchor—you have a vague intention that will fail when life gets busy or motivation wanes.

Similarly, anchoring to habits that occur at variable times creates instability. “After I eat breakfast” works if you always eat breakfast at the same time in the same place. If breakfast happens sometimes at 6am and sometimes at 9am, sometimes at home and sometimes at a café, the inconsistency weakens the stack significantly.

The solution is ruthless honesty about which behaviours truly happen automatically every day. Your real automatic habits might be less impressive than you’d like—brushing your teeth, checking your phone, getting into your car—but their reliability makes them infinitely more valuable as anchors than aspirational behaviours you wish you did consistently.

Stacking Too Many Behaviours at Once

Enthusiasm often leads people to create massive stacks of six, eight, or ten new habits all at once. This overreach virtually guarantees failure. Even if you successfully complete the enormous stack for a few days, the sheer length and difficulty of the sequence can make it unsustainable in the long run.

Your brain can only automate behaviours through repetition, and that process takes time and consistency. Trying to establish too many new patterns simultaneously divides your attention and makes it less likely that any individual habit will become automatic. Each behaviour you add increases the chance that you’ll skip the entire stack on difficult days.

Start with one or two stacked behaviours attached to a reliable anchor. Allow those to become truly automatic before adding anything else. This typically take several weeks (contrary to the popular myth that habits take only 21 days to establish). This might feel slow initially, but it leads to stacks that actually stick rather than ambitious plans you abandon within days.

Making Individual Habits Too Difficult

Another common error is stacking behaviours that are individually too challenging for your current capability. If you’re currently sedentary, stacking “do 50 press-ups” onto your morning routine sets you up for failure. The difficulty of that one behaviour can cause you to skip the entire stack, preventing other easier habits from becoming established.

Remember that your goal initially isn’t to achieve your ultimate objective but to build the behavioural sequence. A tiny version of the habit that you actually perform daily is infinitely more valuable than an ambitious version you skip regularly. Start with “do five press-ups” or even “get into press-up position.” Once that becomes automatic, increasing the number is straightforward.

This principle applies to every behaviour in your stack. Each individual habit should feel almost ridiculously easy, at least initially. The whole stack should take no more than a few minutes to complete in its early stages. As each behaviour becomes automatic, you can gradually scale up the difficulty or duration.

QUICK WIN:

Review your current attempt at habit stacking (or past failed habits). Is your anchor truly automatic? Is your new habit small enough to do on your worst day? If not, shrink it down. “After I brush my teeth, I will do 20 press-ups” becomes “After I brush my teeth, I will do 3 press-ups.” You can always scale up once it’s automatic.

Habit Stacking Examples for Different Goals

Understanding the theory of habit stacking is valuable, but seeing concrete examples helps you envision how to apply the technique to your specific circumstances. Here are proven stacks for common goals.

Morning Productivity Stack

“After my alarm goes off, I will sit up immediately and place my feet on the floor.”

“After my feet touch the floor, I will drink the glass of water on my nightstand.”

“After I drink my water, I will make my bed.”

“After I make my bed, I will do two minutes of stretching.”

“After I stretch, I will write my top three priorities for the day.”

This stack starts your day with a sense of accomplishment and clarity. The physical actions (sitting up, drinking water, making bed) create momentum, the brief stretching wakes up your body, and identifying priorities focuses your mind before external demands flood in.

Healthy Habits Stack

“After I arrive home from work, I will immediately change into exercise clothes.”

“After I change into exercise clothes, I will do ten minutes of movement.”

“After I’ve done ten minutes of movement, I will drink a large glass of water.”

This stack embeds healthy behaviours at the end of your working day. By keeping each individual habit small and attaching it to existing routines, you build a health-supporting lifestyle without requiring sustained motivation or massive time commitments.

Evening Wind-Down Stack

“After I finish dinner, I will take my plate directly to the kitchen.”

“After I put my plate away, I will spend two minutes tidying the main living area.”

“After I tidy, I will prepare my clothes for the next day.”

“After I prepare my clothes, I will review my calendar for tomorrow.”

“After I review my calendar, I will set out my morning coffee supplies.”

This stack transforms your evening into preparation for a smooth morning tomorrow. Rather than waking up to yesterday’s mess and scrambling to get ready, you’ve systematically set yourself up for success. The brief nature of each task prevents the stack from feeling burdensome.

Learning and Growth Stack (distributed throughout the day)

“After I sit down at my desk in the morning, I will read one page of a professional development book.”

“After I close my laptop for lunch, I will listen to five minutes of an educational podcast.”

“After I finish dinner, I will practise my target language for ten minutes.”

“After I get into bed, I will read one chapter of a book.”

This is an example of a distributed stack: it prioritises learning at various times through the day, without requiring large blocks of dedicated time. By distributing short learning sessions across your day and anchoring them to existing transitions, you accumulate significant knowledge and skill development over time.

QUICK WIN:

Choose just one habit stack from the examples above that fits your routine. Write your specific formula: “After I [existing habit], I will [new habit] at [location].” Set a reminder for tomorrow morning to review whether you completed it. Commit to 7 consecutive days before judging whether it works. One stack, one week, that’s all.

Troubleshooting Your Habit Stacks

Even well-designed stacks sometimes fail to stick. When your stack isn’t working, systematic troubleshooting usually reveals the problem and points toward solutions.

The Stack Feels Like a Burden

If completing your habit stack feels like a chore you’re forcing yourself through, the individual habits are probably too demanding. The stack should feel like a natural flow where each action leads comfortably into the next, not a gauntlet you must survive through willpower.

Reduce the difficulty of each stacked behaviour. Cut the duration in half or more. Remove habits from the stack temporarily. Focus on making the sequence feel easy and automatic rather than impressive. Once the flow becomes natural, you can gradually reintroduce complexity.

You Keep Forgetting the Stack Entirely

If you regularly forget to perform your stack, your anchor habit isn’t truly automatic, or the connection between anchor and stacked behaviour isn’t strong enough. Review your anchor—do you genuinely perform it without thinking every single day, or are you choosing an aspirational behaviour you wish were automatic?

Additionally, strengthen the cue by adding environmental triggers. Place a physical object that reminds you of the stacked habit right next to where your anchor habit occurs. If your stack is “after I pour coffee, I will take vitamins,” put your vitamin bottle directly beside the coffee-maker where you can’t miss it.

You Skip the Stack on Busy or Stressful Days

This pattern indicates your stack is too long, too difficult, or poorly timed. On your hardest days—when you’re stressed, tired, or overwhelmed—your stack should be so minimal that skipping it requires more effort than completing it.

Create a “minimum viable stack” version that you commit to performing even on terrible days. If your normal morning stack includes five habits, identify the two most important ones that take less than a minute combined. This minimum version maintains the pattern even when circumstances aren’t ideal, preventing the stack from disappearing entirely during challenging periods. Prioritise keystone habits (habits that have beneficial knock-on effects).

The Compound Effect of Habit Stacking

The true power of habit stacking becomes apparent over time. A few small behaviours attached to existing routines might not seem transformative in isolation, but their cumulative effect over months and years is remarkable.

Consider a modest morning stack: two minutes of stretching, three deep breaths, and writing your top priority for the day. Individually, these habits seem trivial. Over a year, however, you’ve completed over 700 minutes of stretching (nearly 12 hours), taken over 1,000 conscious breaths, and identified your daily priority more than 300 times. These small investments compound into significant physical flexibility, stress management capability, and clarity about what matters.

The compound effect extends beyond the specific habits you stack. Successfully building habit stacks develops your broader capacity for self-regulation and behaviour change. You prove to yourself that you can systematically build new patterns, which increases your confidence in tackling future changes. Each successful stack makes the next one easier to establish.

Moreover, habit stacks often trigger second-order effects you didn’t explicitly design. A morning stretching habit might lead to better posture throughout the day. A daily priority-setting routine might improve your decision-making about how to spend your time. A reading-before-bed stack might reduce your phone usage in the evening. These beneficial spillover effects multiply the impact of your initial stacks.

Start with a single stack anchored to a genuinely automatic habit. Make the stacked behaviour absurdly small – ideally a habit that can be completed in two minutes. Be patient with the process of automation. Then add another stack. Over time, you’ll build a comprehensive system of behaviours that support your goals, all without requiring the motivation and willpower that traditional habit formation demands. This is the practical magic of habit stacking—transforming your daily routine one reliable sequence at a time.

RESOURCES:

Recommended Reading & Tools:

Atomic Habits by James Clear – The definitive habit formation guide Paperback | Kindle| Audible

Atomic Habits Workbook by James Clear – Companion workbook to Atomic Habits Paperback | Kindle | Audible

Tiny Habits by BJ Fogg [link] – Master the anchor moment technique Paperback | Kindle| Audible

Streaks Habit Tracker – Simple iOS habit tracking app

James Clear’s 3-2-1 Newsletter – Weekly habit insights (free)

Resources may contain affiliate links. If you purchase through these links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Related Articles:

The Habit Loop Explained – Understanding cue-routine-reward structure

Why Habits Fail – Troubleshoot when your stacks break down

The Two-Minute Rule – Start absurdly small for lasting change

I'm Simon Shaw, a Chartered Occupational Psychologist with over 20 years of experience in workplace psychology, learning and development, coaching, and teaching. I write about applying psychological research to everyday challenges - from habits and productivity to memory and mental performance. The articles on this blog draw from established research in psychology and behavioural science, taking a marginal gains approach to help you make small, evidence-based changes that compound over time, allowing you to make meaningful progress in the areas you care about most.